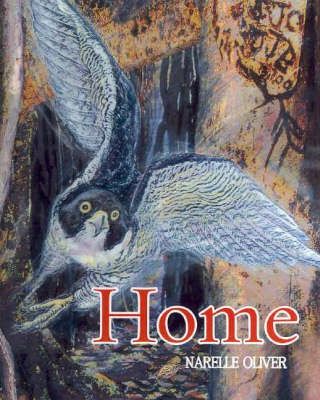

Inspired by the true story of Frodo and Frieda, two peregrine falcons nesting on a waterfront skyscraper in the city of Brisbane, and dedicated to them, Narelle Oliver's ‘Home’ focuses on two days in the lives of a pair of unnamed peregrine falcons, dispossessed of their usual habitat by devastating bushfires, and now making their home among the sheer 'cliffs' of a high-rise city.

There are several challenges for young readers here. The first is that peregrines hunt other birds for food. A potential emotional response to this fact is like that evoked by wildlife documentary films, in which the pursuit and killing of a deer by a cheetah or lion may appear 'cruel'. The natural abilities of the creatures are so unequal, the climax is inevitable, and the killing precise and clinical - and yet human aversion or sympathy is irrelevant. This is a process of survival, 'nature red in tooth and claw', as Tennyson expressed it.

Towards the end of the narrative, the male falcon dives after and kills a beautiful, much smaller bird and takes the 'catch' back to his hungry mate. In the spread immediately after the elided kill, the prey barely looks like a bird at all, as the falcon perches on its dead body, now laid on the high-rise balcony that is the falcons' home. The challenge for young readers is to suspend their sadness and accept the death of one species as the means for another to survive. The dead bird of just meat for two bigger birds that have been struggling to live: no emotional response required.

This inference leads to the second, far more complex challenge. The peregrine falcons have been driven from their natural habitat by bushfires. Although ‘Home’, published in 2006, predates Australia's current awareness of climate catastrophe and the spectre of species extinction, it is impossible to read it now without the widespread belief that such events are the result of human mismanagement of the natural environment. When the falcons flee the burnt, blackened landscape, begin to fly over new vibrant colours and textures in their search for a new home, and come to rest on the ledges and sheer 'cliffs' of a high-rise city built by humans, the book urges its readers to admire the falcons' ingenuity and adaptability. Among the educational resources in the final spread is a quote from biologist Tim Low, praising the peregrine falcon as 'an important symbol of the urban adaptation of wildlife.' And yet the city here is full of images of human beings as threats, not just to wildlife, but also to one another. The hot air balloon with the vast image on its skin of a gigantic bird 'ready to attack' suggests the rapaciousness of advertising. The image frightens the peregrine falcon, but by implication is also frightening to its human prey. The crowding of high-rise office blocks and apartments is a familiar sign of corporate greed and indifference to the idea that the built environment should be life-sustaining. And the sudden launching into the air of a child on a swing, and the stream of shiny high-speed 'beasts' on the traffic lanes crossing the bridge signal not just danger to wildlife, but the potential danger to other humans as well.

So are young readers to join Tim Low in admiring the ability of the falcons to turn a hostile built environment into a new home? Or are they to fear for these immigrants who cannot possibly foresee the danger these new immigrants face in the future? In such an environment, many of even the most resourceful humans are ending up - even now - as symbolic roadkill.

The third challenge confronting young readers of ‘Home’ is the complex layering of meaning in the illustrations and design. Both elements confer exceptional beauty on the word text. First, the use of mixed media makes the visual narrative dynamic, as it shifts from pencil, watercolour, pastel, to collage, linocut and photography, and celebrates rather than hides the use of computer rendering in doing so. The shifting of texture and visual perspective reinforce the theme of adaptability and the frequent aerial shots again predate the now almost cliche use of camera drones in visual narratives - giving both the birds' point of view, and the tantalising possibility that somehow humans may be able to rise above the unlovely aspects of the environment they have built.

There are also metaphorical transformations of the mundane urban environment into poetry. Buildings are 'mountain peaks'. Their concrete ledges and sheer glass walls are 'cliffs' overlooking the river. Seen from above, the rowing teams are many-legged water-striding insects. Small children on playground equipment are like sudden frightening animals. Fast cars are like 'shiny beasts'.

Added to this metamorphosis is the freshness of seeing Brisbane celebrated in a picture book. Once regarded with some embarrassment, if affectionately, as nothing more than a sprawling country town, here it is a glittering, colourful, international city. The reflected light, the posterised colour effects that make the trees and the surface of the river appear both complex and simplified, give it a storybook quality - even the ravaged burnt-out forests appear beautiful, but that irony is problematic. At the same time, these effects occasionally invite comparisons with the graphic arts that have been used relentlessly to sell Brisbane to investors and developers. Finally, the designer's decision to set the word text in Solid Antique font is challenging. In the distinctive descenders for lower case 'g', it scatters prominent round eggs throughout the text, signalling the continuity of life, but this font is oddly elegant and more often associated with human fashion, fine arts and elitism than with survival and the natural environment.

How will young readers respond to this book? There are at least two narratives here: one that seems inspired by the adaptability of species that will survive some of the seemingly insurmountable challenges thrown at them by humans; and another that is far less confident of their survival. Home would make an interesting comparison with Jeannie Baker's ‘Window’ and ‘Belonging’.