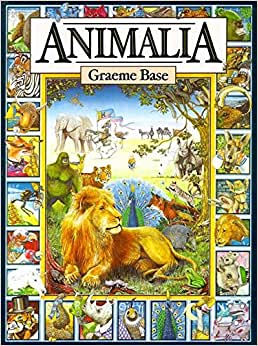

‘Animalia’ has become a lasting favourite among children and parents, not least due to Base’s superbly crafted, extravagant, and vividly realistic illustrations. There has been a colouring book, calendar, a television series, a mobile phone app, and a number of anniversary editions. The book is constructed upon a simple concept electrified by a wild and witty spirit. The idea is to present a traditional visual alphabet book – that is also a teemingly nutty visual dictionary. While ‘Animalia’s’ sheer abundance of objects and animals’ gestures back to a past world of encyclopedias and cabinets of curiosities, it is tempting to see the book as a prescient step into the infinitely variable screen-world of the internet, for it was published only a few years before the advent of the World Wide Web.

Perhaps, though, the most interesting thing about this book is the way it moves between words and images. While there is so much to look at and enjoy, to find and examine, to follow, to savour and admire in the imagery, there is also the alphabetically ordered insertion of names and cultural references under each letter. For instance, while there are plenty of characterful frogs under ‘F,’ there is also Frankenstein’s monster (holding a fork), and a fairy figure in the foreground of the forest. On the following page, under the letter ‘G’ his name not only begins with ‘G’ but takes the form of graffiti. And on that page, there are darker corners of history suggested through faint but distinct images of guillotines, gallows and ghosts – and perhaps a more politically engaged moment when a blonde girl drops her golliwog in order to present a gift to a grenadier who is guarding the instruments of death. Celebrating its own inventiveness, the book achieves the kind of energy and boldness sometimes seen in the twentieth century history of surrealism, with its manifest aim of altering the world through the alchemy of language. Or equally by unpredictable images: when the Surrealist poet Lautréamont famously admired the beauty of a chance encounter of a sewing machine and umbrella on a dissecting table, the way was prepared for ‘Animalia’s’ chance encounters of a duster and a drill with dynamite in a drawer, or a jester, a judge, a javelin and a can of jam around a jug beside a jukebox. Even within the constraints of the alphabet ‘Animalia’ is an infinitely detailed world of jangled juxtapositions.

The invitation to readers to find the figure of Graeme Base somewhere in each picture is an invitation to linger over details and look round corners, under things and into things. Each page of ‘Animalia’ shares with us a new world through its crazily alliterative fun with language (‘Jovial jackasses juggling jugs of jelly in the jungle’ or ‘Crafty crimson cats carefully catching crusty crayfish’) and by the sheer insistence of its realistic details. Under the letter ‘C,’ in the background, convicts play cricket outside a castle with a cannon aimed at them while in the distance we are invited to reflect upon receding visions of a caravan, a circus, a cemetery, a church, and a city.