The original ‘My Place’ for adults was published in 1987, just before Australia’s Bi-centenary. It was a significant autobiographical statement by a then unknown Aboriginal author that was immediately recognised as a reframing of postcolonial Australian history through the eyes of its First Peoples. AB Facey’s ‘A Fortunate Life’ (1981) was the telling of white Australian history by an ostensibly ordinary man, who proved to be anything but ordinary: Facey was hailed as an Australian everyman. ‘My Place’, too, seemed to embrace a whole sweeping story of modern Australia - but this time through the eyes of an Aboriginal observer, who also happened to be a woman. Both perspectives challenged deeply entrenched Australian mythology, so ‘My Place’ was a kind of alternative history, or perhaps a companion piece to Facey’s life writing. Within three years, the publisher realised its potential for young readers, and it was adapted by the doyenne of Australian children’s publishers, Barbara Ker Wilson, into a series of three books: ‘Sally’s Story’, ‘Arthur Corunna’s Story’ and ‘Mother and Daughter’. This is Book 1 of ‘My Place’ for Young Readers: ‘My Place’.

To be fair, the formatting of the book has not aged well, and has a slightly more old fashioned density than contemporary young readers are used to. But coming back to Sally Morgan 30 years after first hearing her voice is wonderful. It’s like meeting an old friend, or a sorely missed member of the family. ‘Sally’s Story’ absolutely crackles with energy: the author’s imagination, her understanding of both adults and children, her sense of humour, her determination to have her Aboriginal heritage acknowledged. In those 30 years she has become as well known for her story-telling in pictures as well as words, and astute readers in 1987 would have sensed that on every page. The hospital patient with hair ‘like toothbrush nylon’, the flaring of ‘Miss Roberts’s large sensitive nostrils’, the ‘swirled pattern of the linoleum like Mum’s marble cakes’. And then the other sense impressions: the silence of a mother and the whistling of a father, the acrid smell of Nan’s kerosene body rubs, and a child’s fear that as a chain smoker, Nan’s whole body might one day catch alight.

The abridging of adult texts for children is justifiably treated with suspicion: too of-ten a story is ‘dumbed down’, and if readers are not ready for the full original version, perhaps they should wait until they are. It’s not as if excellent stories for young readers are scarce. Surprisingly, though, in the case of ‘Sally’s Story’, Barbara Ker Wilson has done ‘My Place’ a favour. By trimming down some of the adult language Morgan inevitably used as she looked back on her childhood in the original, here Ker Wilson has amplified the unmediated voice of an Australian child - it’s unforgettable and it moves along at an exhilarating pace. The now classic answer Sally’s mother gives to the persistent question about the family’s cultural heritage, ‘Tell them we’re Indian’, drives this child’s determination to get further answers from the adults. And, as is frequently the case, the answers are instead given by other children. ‘We’re boongs!’ Coming from a younger sister, these words that Sally wants to hear - and doesn’t want to hear - set her head ringing.

So for class research into the silences around cultural identity (particularly, but not exclusively Aboriginal), ‘Sally’s Story’ is an accessible and inspiring introduction. But equally nuanced is the story of a child’s relationships with adults. Whereas Sally’s mother is stoic, practical and hard working, her father is self-destructive and unreliable, and yet the portrait of his erratic behaviour is a loving one, softened by a child’s intuitive understanding of what the war has done to him. And for all the reservations about Nan’s bush cures, like binding pepper into open wounds and applying it liberally in a whole range of emergencies, Nan comes across as a com-passionate portrait of an older generation trying to come to terms with a rapidly changing world. Doubly marginalised. If young Sally expresses her reservations with laughter and skepticism, they are nevertheless held with respect and love.

And that finally is why the original ‘My Place’ broke new ground. To the stereo-typed conventional white narrative of Aboriginal Australians, it added determination, success, humour, love, playfulness, and the perspectives of women and children, while maintaining a fight for truth and justice that continues. So it cannot be dismissed for any perceived partisan politics or narrowness of vision. It is some-times hard to believe that movements such as Black Lives Matter and Me Too are still needed, but in that context making ‘Sally’s Story’ available to young readers is more important than ever.

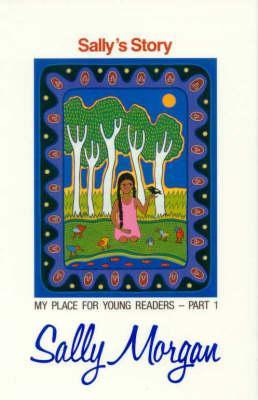

Series: ‘My Place’ for Young Readers - Part 1