Title

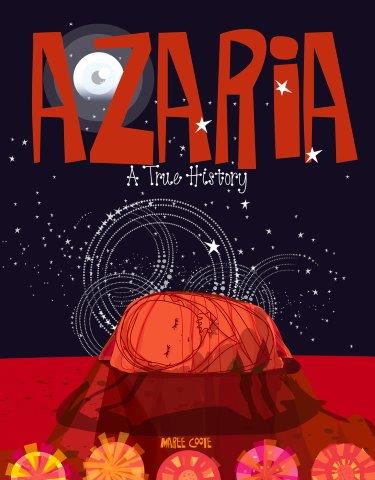

Azaria : A True History

Author

Maree Coote

Illustrators

Maree Coote

Publisher, Date

Melbournestyle Books, 2020

Audience

Primary, Secondary, Upper Primary

ISBN

9780648568407

Language

English

Add to Favourites

-

Subjects

- Art motifs

- Babies

- Death

- Dingo attacks

- Dingoes

- History

- Missing children

- Religion

- Tracking

- Uluru / Ayers Rock (South Central NT SG52-0200)

-

Annotation

For adults who remember the 1980 death of two-month-old Azaria Chamberlain that destroyed a family and divided the nation, Azaria’s black dress and red booties are still among the most controversial exhibits in the National Museum of Australia, so the question of whether her death is suitable subject matter for a picture book is not surprising. However, by acknowledging the Anangu peoples, custodians of the land around Uluru, where Azaria was taken by a dingo, author-illustrator Maree Coote is not simply observing protocols. The narrative highlights the role of Indigenous trackers in confirming the account given by Lindy Chamberlain, Azaria’s mother, thereby freeing her from jail and quashing her conviction for murder.

The subtitle ‘A True History’ indicates that the real subject of this book is the power of disinformation and rumour, and the role of the press in dividing a community. Set forty years before the phrases ‘fake news’ and ‘echo chamber’ were to become catchcries around the world, ‘Azaria: A True History’ is about the confusion of truth and fiction that destabilises both scientific fact and the law, and is therefore a timely text for classroom discussion. It does remain ‘A’ true history. The role of Azaria’s father and the family’s religion, for example, are barely touched on. In archival footage Lindy Chamberlain says, ‘A dingo’s got my baby’, but here it is rendered ‘A dingo has taken my baby’ – no doubt to avoid the seemingly endless repetition of that line in popular culture, made infamous by Meryl Streep’s odd Australian accent in the 1988 film adaptation ‘Evil Angels’.

Maree Coote narrowly avoids the charge of cultural appropriation in the illustrations, landing somewhere between commercial graphic art, animation and mid-century illustration of fairy tales. The moon on the front cover is an oddly mechanical eye that accuses the reader but is somewhat softened by the staring eyes on the wings of Bogong moths throughout. The sleeping baby is at times a swaddled babushka, hiding layers which the reader might prefer not to unwrap, and at other times is a chrysalis. Coote constructs the dingo’s attack as part of an ongoing natural cycle, just like the birth of moths and their flight towards the blinding lamplight that is at once here theatrical and a reminder of incarceration and surveillance. Perhaps the destructiveness of gossip and disinformation is also being framed, alarmingly, as part of a natural cycle. Reviews of ‘Azaria: A True History’ have praised the bold palette, but one result of its stark drama may be to restrain emotional realism, to fold the narrative back into ongoing tropes of myth and fairy tale, and to focus instead on the complex surface of intellectual discourse about the nature of truth.

-

Teaching Resources

- ‘Azaria: A True History’ Melbournestyle.com.au Includes links to 2 radio interviews and an art exhibition of the illustrations, March 2020 http://www.melbournestyle.com.au/AZARIA.html

- ‘Dingo’s Got My Baby’: Trial by Media, The New York Times 18 November 2014 (useful perspective on non-Australian responses) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hwd0iomlM1Y&t=638s

- Excerpt from ‘The Country of Lost Children: An Australian Anxiety’ by Peter Pierce, Cambridge University Press, 1999 https://books.google.com.au/books?id=JCym_PWkEIIC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ViewAPI&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ‘Dingo ate my baby’ (references to this line in popular culture) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dingo_ate_my_baby

- Children’s Book Daily review of Azaria: A True History https://childrensbooksdaily.com/book_reviews/azaria/

- Rebecca Cameron video discusses Azaria: A True History https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2OYV3G70VK8